By Andrea Goto Photography by Chia Chong

When I was just a kid growing up in the Pacific Northwest, Dad would drive us down to the waterfront and through the seediest part of town to a crumpled little building called The Shrimp Shack. There, sturdy men with big hands and loud voices who knew my father’s name called out orders, wrapped our oysters and tossed them into our open hands.

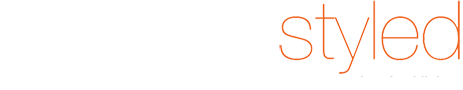

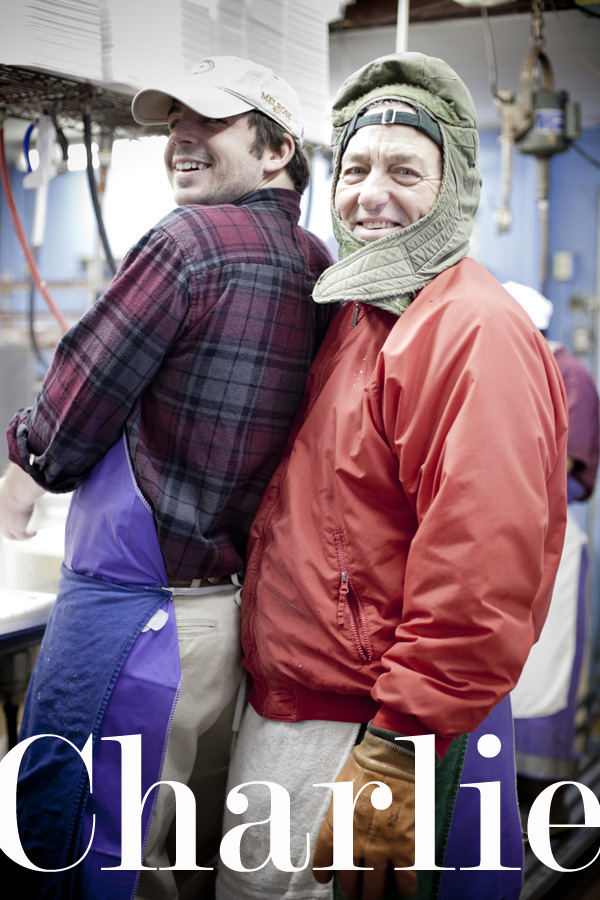

There’s a nostalgic quality to Russo’s that reminds me of The Shrimp Shack and, consequently, a simpler time when good men made a living through honest, hard work. Maybe it’s because this family business has been in operation since 1946. Or maybe it’s because they display fish in vintage freezers and tack hundreds of curling, sun-washed photographs to the walls. Whatever it is, this place is informed by character; the embodiment of this character being Charlie J. Russo, Jr. himself.

Charlie is the kind of Savannahian I like best. In a thick, rolling drawl, he refers to his father as “Daddy,” the government as “monkey business,” and an alcoholic as someone who “likes to have a drink”—all of which makes me feel like I’m being bathed in sunshine, though I’m not sure why. I can’t place Charlie’s age and I have a feeling it would be impolite to ask, even though he’d tell me. He’s an old soul, but his ice-blue eyes, flushed cheeks and backwards baseball cap give him a youthfulness I’d like to bottle up for future use. Perhaps the best way to describe Charlie is to call him “intent.” He’s intent on doing his job and intent on giving you want you want, whether it’s a perfectly filleted flounder or an exacting lesson on local history.

I learn a lot about Savannah from Charlie, or “Chas” as it’s written on his apron bib. He sits me down and rattles off the story of Russo’s beginnings like he’s in a horse race, casting family and street names around like an expert fly fisherman. He tells me about the Rayola family who taught his daddy about the seafood business, the Sadler’s who ran supermarkets around town, and “the blacks that lived out there in Pin Point” (birthplace of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, he tells me) who caught shrimp for a man named Mr. Von until one day the government came along and changed the crabbing regulations, essentially shutting down a 75-year-old business.

Charlie has run into his own problems with the government interfering with his ability to get the local products his customers want. “Every time you turn around, they’re clipping your heels,” he says. Though he gets some seafood locally, like shrimp and shad, he explains how you can no longer catch red snapper, grouper or sea bass on the east coast. “There’s more sea bass out there in Georgia than you can shake a stick at,” he says, shaking his head. When customers who don’t know better turn their noses up at delicious salmon flown in from Norway, fish from Chesapeake Bay, or crab imported from Ecuador, Charlie educates them on the ins and outs of the highly regulated fishing industry. But regardless of where he gets his seafood, Charlie makes one promise: “I guarantee you, you come in here, you get it, it’ll be as good if not better than anything you’ve ever had.”